Among carbonyl compounds, hexafluoroacetone behaves in a way that surprises even experienced chemists: it readily forms a stable hydrate (a geminal diol) in the presence of water. This is not a trivial side reaction or an impurity issue—it is a direct consequence of the molecule’s extreme electronic structure. Understanding why hexafluoroacetone hydrates so easily is essential for reaction design, moisture control, storage strategy, and correct interpretation of analytical data.

Hexafluoroacetone forms a hydrate because its carbonyl carbon is extraordinarily electrophilic, and the resulting geminal diol is strongly stabilized by the powerful electron-withdrawing effects of two CF₃ groups, shifting the equilibrium toward hydration.

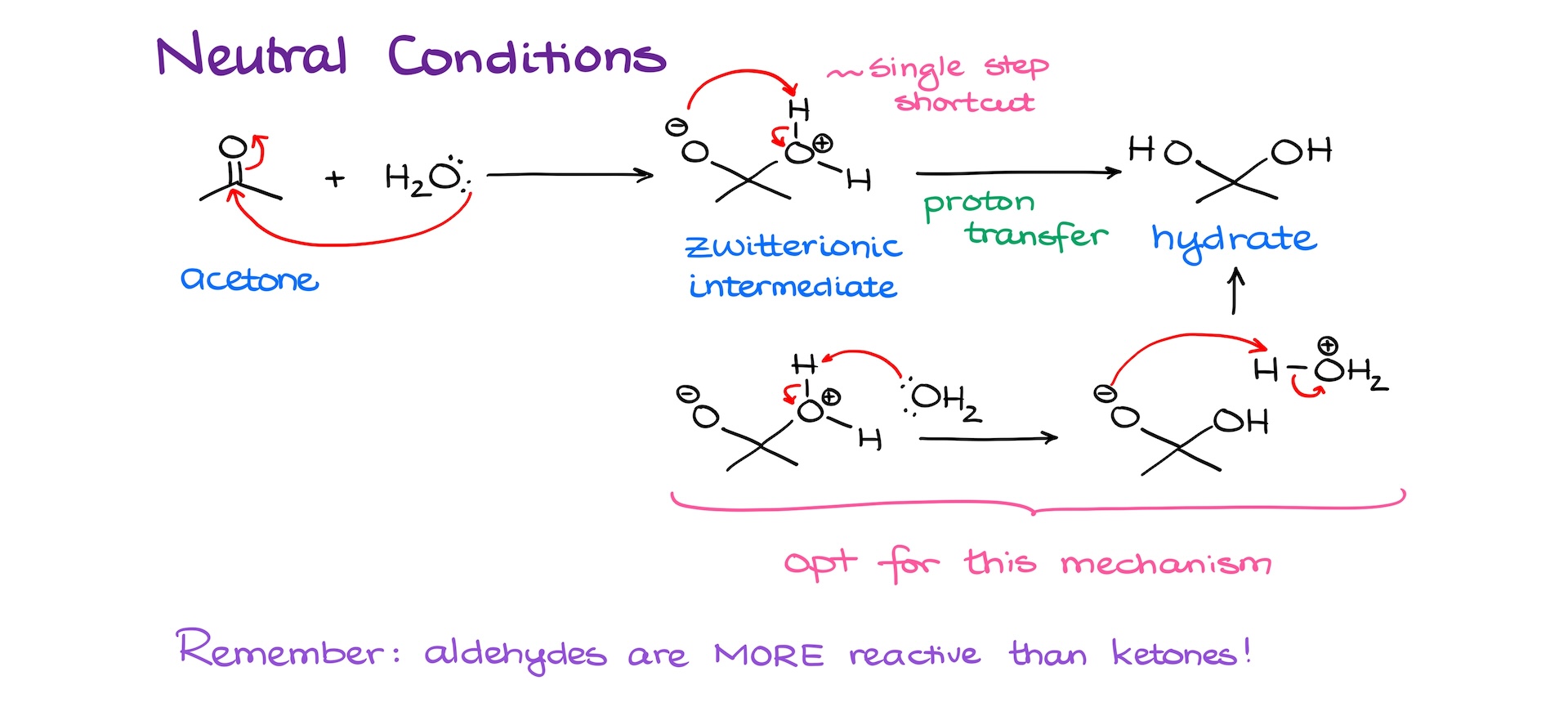

The general concept: carbonyl hydration equilibrium

All aldehydes and ketones exist in equilibrium with their hydrated forms when water is present. In most ketones, however, this equilibrium lies overwhelmingly toward the carbonyl form, because hydration produces a less stable geminal diol.

Hexafluoroacetone is a dramatic exception. In this molecule, the equilibrium is shifted significantly toward the hydrate, meaning that in moist environments the hydrated form can dominate.

This unusual behavior is explained entirely by electronic effects.

Extreme electrophilicity invites water addition

Water is a weak nucleophile, and under normal circumstances it adds slowly and reversibly to carbonyl compounds. Hexafluoroacetone changes this rule because its carbonyl carbon is exceptionally electron-deficient.

Two CF₃ groups exert enormous inductive electron-withdrawing effects, pulling electron density away from the carbonyl carbon. As a result:

- The carbonyl carbon becomes strongly positively polarized

- Even weak nucleophiles such as water can attack efficiently

- The activation barrier for hydration is very low

This makes hydration not only possible, but fast.

Stabilization of the hydrate by CF₃ groups

Forming a hydrate is only half the story. For hydration to be favored, the hydrate itself must be stabilized. This is where CF₃ groups play their second critical role.

In the geminal diol formed from hexafluoroacetone:

- Negative charge density develops on oxygen atoms

- Strong electron-withdrawing CF₃ groups stabilize this charge

- The diol is less prone to revert back to the carbonyl

In effect, CF₃ groups stabilize the product of hydration more than they destabilize the starting ketone, pushing the equilibrium toward the hydrate.

Comparison with ordinary ketones

The contrast with acetone makes the effect clear:

| Compound | Carbonyl substituents | Hydration tendency |

|---|---|---|

| Acetone | CH₃ / CH₃ | Negligible |

| Trifluoroacetone | CF₃ / CH₃ | Moderate |

| Hexafluoroacetone | CF₃ / CF₃ | Strong |

Replacing electron-donating methyl groups with electron-withdrawing CF₃ groups completely reverses the hydration behavior.

Hydrogen bonding further stabilizes the hydrate

Once formed, the hydrate of hexafluoroacetone can engage in strong hydrogen bonding with surrounding water molecules. The diol structure allows:

- Internal hydrogen bonding

- External hydrogen bonding to solvent water

These interactions further lower the free energy of the hydrated form, especially in moist or aqueous environments.

Thermodynamic and kinetic reinforcement

Hydration of hexafluoroacetone is favored both kinetically and thermodynamically:

- Kinetics: Low activation energy due to high electrophilicity

- Thermodynamics: Strong stabilization of the hydrate

This dual reinforcement explains why even trace moisture can significantly alter the chemical form present.

Practical implications for handling and synthesis

Because hexafluoroacetone hydrates so readily, moisture control is not optional. In practice:

- Dry systems are mandatory for reproducible reactions

- Apparent “loss of reactivity” may be hydrate formation

- Spectroscopic data can change depending on hydration state

- Storage and transport must minimize water exposure

In some syntheses, controlled hydrate formation is deliberately exploited. In others, it must be strictly prevented.

Why hydrate formation matters industrially

From an industrial perspective, hydrate formation:

- Alters effective concentration

- Changes vapor pressure and volatility

- Modifies reactivity toward nucleophiles

- Can affect downstream yield and selectivity

Ignoring hydration behavior often leads to unexplained variability between laboratory and plant-scale results.

Why this behavior is difficult to avoid

Few structural changes can suppress hydration without also destroying the desired reactivity of hexafluoroacetone. Reducing CF₃ content reduces electrophilicity and hydration—but also removes the very properties that make the compound valuable.

As a result, hydration is not a flaw; it is an intrinsic feature of the molecule.

Final summary

Hexafluoroacetone forms a hydrate because two CF₃ groups make its carbonyl carbon extremely electrophilic and strongly stabilize the resulting geminal diol. This shifts the carbonyl–hydrate equilibrium toward hydration, even with weak nucleophiles like water. Hydrogen bonding and charge stabilization further reinforce this effect.

This behavior explains why hexafluoroacetone is both highly reactive and highly sensitive to moisture—and why professional handling and process design are essential.

A practical note from industry experience

In real fluorochemical operations, unexplained inconsistencies involving hexafluoroacetone are often traced back to uncontrolled hydration. Teams that explicitly manage water content achieve predictable, high-yield outcomes; teams that ignore it struggle with variability.

Talk to Sparrow-Chemical about fluorochemical intermediates

If you are working with hexafluoroacetone and need guidance on moisture control, storage, or reaction design, Sparrow-Chemical provides application-driven technical support and reliable global supply. We help customers manage highly electrophilic fluorochemical intermediates with confidence. Visit https://sparrow-chemical.com/ to discuss your application with our technical team.